How to choose between an inboard and an outboard engine for your boat: differences between an inboard and outboard engine and selection criteria

Not sure whether to go inboard or outboard? Fair — this choice affects everything: handling, maintenance, space onboard, seakeeping, and budget. This guide breaks down the differences between an inboard and outboard engine, with practical criteria to match your boating program.

- What’s the difference between an inboard and an outboard engine?

- How propulsion works: shaft, drive, rudder…

- Differences between an inboard and outboard engine: what really changes

- Pros & cons: performance, comfort, onboard space

- Reliability: which boat engine is truly the most reliable?

- Service life: inboard vs outboard (hours, use, maintenance)

- Which is “better”? Choose based on your boat and your use

- Maintenance & costs: what you’ll pay (or avoid) over 5 years

- Repair, replace, upgrade: new blocks, remanufactured, packages

- Quick comparison table: inboard vs outboard (choice criteria)

- Quick FAQ

What’s the difference between an inboard and an outboard engine?

The first difference is simply where the engine sits. An outboard is mounted outside on the transom: a compact unit combining engine + midsection + gearcase + propeller. An inboard sits inside the hull (engine bay): only the propulsion hardware (shaft + prop, or a drive depending on the setup) ends up under/behind the boat.

Second key difference: steering. With an outboard, the whole engine pivots to direct thrust. With many shaft-drive inboards, the engine doesn’t pivot — you steer with a rudder behind the prop, which behaves differently at low speed.

How propulsion works: shaft, drive, rudder…

Outboard: “powerhead + gearcase” (all-in-one)

An outboard is an integrated package: powerhead, midsection, gearcase, and propeller. You steer by turning the whole unit. Practical bonus: trim/tilt lets you lift the engine (useful in shallow water, at the dock, and to reduce corrosion/fouling).

Inboard: “engine inside, propulsion underneath”

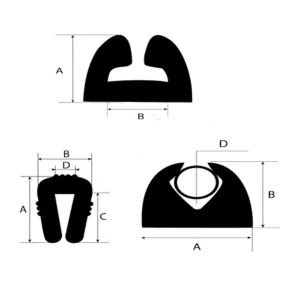

Inboards come in several architectures:

- Straight shaft (D-Drive): engine facing aft, near-direct shaft to the prop. Simple, robust, minimal losses.

- V-Drive: gearbox redirects the shaft aft (V-shaped drivetrain). Better packaging, a bit more complexity.

- Sterndrive (Z-Drive): engine inside, steerable drive outside — a hybrid feel between inboard and outboard.

- Jet drive: impeller + waterjet (common on small fast boats/PWCs), no exposed prop.

Differences between an inboard and outboard engine: what really changes

- Docking & handling: outboards are often more responsive in marinas (vectorable thrust). Shaft-drive inboards require more anticipation.

- Seakeeping & balance: inboards put weight low and central (stability), while outboards load the stern (trim and onboard weight distribution matter more).

- Space onboard: outboard = more interior space. Inboard = engine bay volume.

- Mechanical access: outboard = easy access. Inboard = sometimes tight access (your knees will remember).

- Shallow water: outboard wins (tilt up). Inboard requires more caution (running gear under the hull).

- Noise / vibration: inboards can feel more muted (engine enclosed), all else equal.

Pros & cons: performance, comfort, onboard space

What’s the main advantage of an outboard?

Practical versatility: easy access, easier repower, and trim/tilt to adapt (shallow water, trailering, storage). If your boating is “day trips + marinas + trailer + mixed depths”, outboards are hard to beat.

Why choose an inboard?

If you want comfortable cruising, stability, and a planted feel at cruising speed, inboards make mechanical sense: low center of gravity, strong torque (often diesel), and drivetrains designed to push heavier boats efficiently.

They can also be appealing for towing sports: with many setups, the prop is under the boat and away from the swim platform area, which can feel reassuring when towing.

Reliability: which boat engine is truly the most reliable?

The honest answer: the most reliable engine is the one that’s properly matched to the hull and maintained consistently.

- Shaft-drive inboard: simple, robust architecture; great endurance.

- Outboard: excellent reliability with easy access — provided you stay on top of flushing, anodes, and service intervals.

- Sterndrive: great performance feel, but more components (bellows, U-joints, drive) — reliable with care, expensive if neglected.

Rule of thumb: less complexity is more forgiving — but outboard accessibility often prevents small issues from becoming big failures.

Service life: inboard vs outboard (hours, use, maintenance)

Hours matter more than calendar years (a 10-year-old engine can be “young” if lightly used, or the opposite).

- Inboard lifespan: in leisure use, a well-maintained inboard often reaches thousands of hours. Diesels are known for long, steady cruising endurance.

- Outboard lifespan: modern 4-strokes hold up very well; longevity depends mainly on corrosion control, clean fuel, cooling system service (impeller), and regular oil/filter work.

What “kills” engines isn’t age — it’s overheating, corrosion, skipped oil, and the classic combo: “small alert ignored + you go anyway”.

Which is “better”? Choose based on your boat and your use

So… are inboards or outboards “better”? Depends on your reality, not the brochure.

Choose an outboard if…

- You mostly do day trips, with frequent docking/launching.

- You want easy access and simpler routine maintenance.

- You run in shallow water or store/trailer your boat.

Choose an inboard if…

- You prioritize cruising comfort, stability, and range.

- Your boat is heavier/more livable, and you plan to go farther.

- You accept more technical maintenance (or have pro support).

Want to avoid the classic “too small / too big” mistake? This guide helps: Which engine should you choose for your boat (guide).

Maintenance & costs: what you’ll pay (or avoid) over 5 years

Cost isn’t just purchase price — it’s access + service intervals + downtime.

- Outboard: routine service is straightforward (oil, impeller, anodes, plugs, filters). Tilting up can reduce fouling and corrosion while moored.

- Inboard: access can be tight; more systems live “inside the boat” (cooling, exhaust, ventilation). Gasoline setups demand strict ventilation/fume safety habits.

More engine resources here: Engine block (topics & resources).

Repair, replace, upgrade: new blocks, remanufactured, packages

When an engine starts eating your budget, three practical paths usually make sense:

- Start fresh for long-term peace of mind: New marine engine blocks | Compatible with Volvo, Mercruiser….

- Optimize budget without rolling the dice: Remanufactured marine engine block | Reliable solution at a lower cost.

- Go turnkey with a ready-to-install solution: Marine engine packages | Complete marinised kits, all brands.

If you’re staying with external propulsion (repower, twin outboards, etc.): Outboard engines for boats | Full petrol 4-stroke range.

Quick comparison table: differences between an inboard and outboard engine

| Choice criteria | Outboard | Inboard |

|---|---|---|

| Placement / space | Mounted outside (transom): saves interior space, adds weight aft. | Inside the hull: uses an engine bay, lower/central mass. |

| Dock handling | Very responsive: pivoting thrust helps manoeuvring. | Shaft drive: more inertia; rudder + reverse can be less “point-and-shoot”. Sterndrive feels closer to outboard. |

| Seakeeping / stability | Good depending on hull; more sensitive to loading and trim. | Often excellent: low/central weight, planted ride in chop. |

| Comfort (noise / vibration) | Typically louder (exposed engine), more vibration felt. | Often quieter: engine enclosed, better for long cruises. |

| Shallow water | Major advantage: trim/tilt up to avoid hits. | More exposed running gear under the hull. |

| Maintenance access | Easy access, faster interventions. | Sometimes tight access; more systems inside the boat. |

| Lifetime costs | Often lower routine service cost; repower is simpler. | Often higher labour/access costs; strong endurance for cruising. |

| Fuel efficiency | Variable: modern 4-strokes are efficient; setup matters (prop/height/trim). | Often diesel on cruisers: strong torque and steady cruise efficiency, longer range. |

| Performance feel | Great on light hulls: punchy acceleration and versatility. | Excellent for heavier boats: torque and stable cruise; depends on architecture. |

| Repair / replacement | Repower is comparatively straightforward; twin outboards possible. | More involved: integration, alignment, peripherals, yard work. |

| Best use case | Day boating, fishing, trailering, mixed depths, simplicity. | Cruising, liveaboard, longer runs, comfort and stability. |

| User profile | Beginner-friendly (handling + maintenance). | Great if you accept more technical upkeep or pro support. |

Quick FAQ

Can you “upgrade” an outboard to make it perform better?

Yes — and most gains come from setup, not “tuning”. The most useful optimizations are:

- Choosing the right prop (pitch/diameter/blade count): often the best cost-to-gain lever.

- Setting engine height (anti-ventilation plate): too low = drag; too high = ventilation and slip.

- Optimizing trim and onboard weight distribution (bad loading costs speed and fuel).

Be cautious with ECU flashes/“de-restricting”: mechanical stress, compliance, insurance — and sometimes questionable real-world gains.

Can you run twin outboards?

Yes, and it’s common on some fishing boats, RIBs and larger open hulls. Main benefits:

- Redundancy: one issue doesn’t necessarily end the day.

- Low-speed control: twin thrust can help in tight marinas (depending on controls).

- Power distribution: sometimes smarter than one very large engine.

Key watch-outs:

- Transom capacity (weight + loads) must be adequate/reinforced.

- Steering: tie bars, hydraulic steering, alignment — installation quality matters.

- Props: counter-rotating setups (when available) can clean up handling.

- Budget: purchase and maintenance are effectively doubled.

Which prop is best for speed, hole-shot and fuel economy?

Quick logic: pitch impacts RPM and top speed, diameter impacts bite/torque, and blade count impacts grip (4-blade often improves control and planing, sometimes with less top-end). A well-chosen prop helps you:

- keep WOT RPM within the recommended range,

- improve planing and midrange response,

- avoid fuel burn caused by lugging or over-revving.

Ventilation/cavitation (“it slips”): how do you fix it on an outboard?

If the prop starts pulling air, RPM rises without speed. Common causes include:

- Engine too high (or poor trim angle),

- Wrong prop (insufficient bite),

- Disturbed water behind the hull (turbulence, deformations, poorly placed accessories).

Fixes: verify mounting height, adjust trim, consider a prop with more grip (sometimes 4-blade), and make sure the setup isn’t sucking air in turns or chop.

Outboards in saltwater: how do you really reduce corrosion?

Saltwater doesn’t forgive, but routines work:

- Freshwater flush (especially the cooling circuit) after use,

- Correct anodes and timely replacement,

- Clean fuel (water separator + filters),

- Tilt up at the dock when appropriate to reduce fouling and electrolysis,

- regular checks: impeller, thermostats, gearcase oil, bellows depending on configuration.

Can you over-power a boat?

You can try — but you must respect max rated power (plate/docs), transom capacity, and insurance constraints. Over-powering can make a boat harder to balance, less safe, and not necessarily faster if hull/prop/setup don’t match. Often it’s smarter to validate height/prop/load/hull condition first.

When does a full engine solution make more sense than ongoing repairs?

If issues become recurrent, compression is down, or you keep stacking “never-ending” fixes, it can be more rational to reset with a clear base: new, remanufactured, or a turnkey package depending on the project.