Which engine should you choose for your boat? (Choosing a boat engine: a technical & practical guide)

Between dockside opinions and unreadable spec sheets, picking an engine can quickly feel stressful: fear of being underpowered, burning too much fuel, or ending up with a poorly balanced setup. This guide lays out a clear (but serious) method to make the right choice: real-world use, hull constraints, key mechanical criteria, budget, and practical benchmarks for 4 m, 5 m and 6 m boats.

- Why engine choice changes everything (safety, comfort, budget)

- Choosing a boat engine: a method that avoids common mistakes

- Power, torque, weight: what actually moves a boat

- Outboard, inboard, sterndrive: which layout makes the most sense?

- Which engine for a 4 m, 5 m, or 6 m boat? Practical benchmarks

- Which boat engine is the most reliable? (the real answer)

- New, used, reconditioned: what to choose for your goal

- Value for money: where profitability really comes from

- Checklist: questions to answer before buying

- Quick FAQ

Why engine choice changes everything (safety, comfort, budget)

An engine is not “just horsepower.” It is a balance between the hull (shape, weight, drag), your real boating program (distance, chop, towing, fishing), and very practical constraints: onboard load, transom height, available space, maintenance, and parts availability.

When the setup is coherent, the boat planes cleanly, fuel use stays more stable, noise drops, and handling feels safer. When it is not, the boat labors, cruise revolutions stay too high, wear accelerates… and fuel bills tend to get painful.

Choosing a boat engine: a method that avoids common mistakes

The right starting point is the boat (and how it is used), not the engine. Before looking at a brand or displacement, lock down four points: the allowed power range, the load the transom can safely carry, transom height (and therefore shaft length), and a realistic loaded weight in real conditions.

Only then does the choice become logical: pick a power level that allows comfortable cruising without running flat-out, choose a drive setup that matches the job (torque versus speed), and keep the overall layout consistent with onboard space and maintenance access.

Power, torque, weight: what actually moves a boat

Power shows potential, but what turns that potential into real behavior on the water is torque, the gear reduction, and the propeller. An engine can look strong on paper yet feel disappointing if the propeller and gearing do not match the program (load, chop, towing, and so on).

A classic trap is “saving money” by going too small. In practice, an underpowered engine spends its life at high revolutions to compensate for drag—rarely good for fuel use or longevity.

“An engine that is not powerful enough will lead to excessive fuel consumption.”

Another often-overlooked factor is engine weight. On small hulls, an extra 20–40 kg on the stern can change running attitude, delay planing, increase time spent climbing onto plane (and fuel use), and make the boat feel stern-heavy in waves. That is why simple “X horsepower for X meters” rules are not enough: loaded weight matters as much as length.

The technical specs that truly matter (and why)

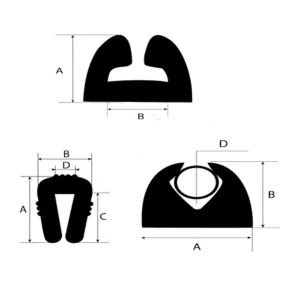

Shaft length (short/long/extra-long): if the prop ventilates (too high) or drags (too low), performance collapses. A cavitation plate that sits close to the hull bottom line (depending on the boat) prevents many issues.

Cruise revolutions: a healthy setup cruises without “screaming.” If cruise speed already requires very high revolutions, it often signals a mismatch in power or propeller selection.

Cooling and corrosion: in saltwater, freshwater flushing, sacrificial anodes, and a healthy cooling circuit are non-negotiable. The best engine on paper loses value quickly if maintenance is ignored.

Controls and ergonomics: tiller or remote controls, manual or electric trim adjustment, alternator output, instrumentation—small details that massively change daily comfort (and docking safety).

Outboard, inboard, sterndrive: which layout makes the most sense?

For most small and mid-size boats, an outboard remains the simplest solution: direct access, easier replacement, generally more straightforward maintenance, and an excellent power-to-weight ratio. It is also the most common setup on RIBs and open boats.

An inboard (engine installed inside the boat) becomes relevant when comfort, stability, or higher power levels are priorities. The trade-off is more constrained access and potentially more technical maintenance.

A sterndrive (inboard engine plus drive unit) can deliver strong performance and a clean integration, but it requires close attention to the drive unit (boots, corrosion, sealing). It is not “better” or “worse”—it is a set of compromises.

Which engine for a 4 m, 5 m, or 6 m boat? Practical benchmarks

The ranges below are meant to frame a first estimate. The final reference should always be the builder’s plate (maximum power) and your real loaded weight (people, fuel, anchor gear, cooler, equipment). Two boats of the same length can require very different power depending on hull design and weight.

Which engine for a 4 m boat?

At 4 m, hulls are often light. For calm cruising or fishing, modest power can be enough. But if the boat regularly carries several people, runs in chop, or needs to get onto plane decisively, choose a power level that allows clean planing without struggle.

Practical benchmark: a range around 15 to 40 horsepower covers many cases, but load and hull shape can push the need up or down. On this size, engine weight and correct shaft length matter a lot.

Which engine for a 5 m boat?

At 5 m, versatility increases… and mistakes cost more. This is often where owners want to do everything: cruising, slightly more offshore trips, and sometimes light towing sports. The engine should keep good response under load without living at the top of its range.

Practical benchmark: 50 to 90 horsepower is common depending on hull type. If towing is part of the plan, torque and quick planing become priorities.

Which engine for a 6 m boat?

At 6 m, loaded weight increases (fuel, gear, sometimes a small cabin). Expectations for comfortable cruising also rise. The engine should hold an easy cruise speed with a safety margin when conditions deteriorate or load increases.

Practical benchmark: 90 to 150 horsepower is frequent, with heavier boats sometimes needing more and optimized hulls sometimes needing less. On this size, propeller choice and trim adjustment have a real impact on fuel use.

Which boat engine is the most reliable? (the real answer)

Reliability is not a logo. A “legendary” engine can become problematic if maintenance is poor, installation is wrong, or it is used far outside its efficient operating range. Conversely, an engine that is correctly sized, flushed after saltwater use, maintained properly, and supported with readily available parts can stay reliable for a very long time.

For a confident purchase, prioritize: a strong service network nearby, a clear maintenance history (when buying used), a setup aligned with your boating program, and parts you can source quickly. In boating, reliability is often a system (engine + installation + maintenance), not a myth.

New, used, reconditioned: what to choose for your goal

New: best when peace of mind matters most and you want a clean baseline for multiple seasons.

Used: attractive when history is clear (invoices, hours, maintenance, winterization). The main risk comes from “low-hours” engines that were stored poorly.

Reconditioned: useful when you want a mechanically solid baseline without paying full new pricing—especially for inboard projects—provided you know exactly what was inspected and replaced.

Value for money: where profitability really comes from

The “right price” is not the engine price alone—it is the cost of ownership: fuel use at cruise speed, yearly maintenance, parts availability, and hull compatibility. Too little power can be expensive at the pump (and in wear), while a well-matched, properly propped engine often runs more efficiently.

As a rough benchmark: a small portable outboard like the Honda 2.3 hp is shown around €983.04 incl. tax, while a Honda 50 hp is shown around €8,199 incl. tax. For higher power, a Honda 135 hp is shown around €18,439.20 incl. tax.

For inboard projects, when the real question is “reset the core engine” rather than replace peripherals, a reconditioned long block can be rational: for example, a reconditioned GM454 block is shown around €11,940.00 incl. tax. These amounts are indicative; the product pages remain the best reference to confirm current pricing.

Solutions to consider (parts & complete sets)

- New boat engine blocks | Compatible with Volvo, Mercruiser…

- Reconditioned boat engine block | A reliable marine solution for a lower budget

- Boat engine packs | Complete marinized kits for all brands

- Outboard boat engines | Full gasoline 4-stroke range

Checklist: questions to answer before buying

An engine should be chosen as part of a complete setup. This checklist helps avoid “impulse buys” that later cost performance or maintenance.

- What is the real program: fishing, coastal cruising, towing sports, professional use, frequent shuttles?

- What minimum and maximum power does the builder specify?

- What is the real loaded weight (people + fuel + gear), not just “empty” weight?

- What is the transom height: correct shaft length and coherent installation?

- What is the target cruising style: speed and comfort, not only top speed?

- Is service access realistic: workshop nearby, parts availability, maintenance budget?

- New, used, or reconditioned: is the priority peace of mind, budget, or a mechanical reset?

Summary table

| Decision | What to check | Simple rule | What it ensures | Typical mistake |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Use | Cruising, fishing, towing sports, professional use | Define one primary use + one secondary use | A coherent engine choice (response, comfort, fuel use, features) | No priorities → average results everywhere |

| 2) Power | Builder range + real loaded weight | Stay within the range and size for full load | Clean planing, safety, more stable fuel use | Going too small → high revolutions and high fuel burn |

| 3) Layout | Original architecture of the boat | Stick with the intended layout (outboard or inboard) | Mechanical compatibility, realistic maintenance, reliable install | Changing architecture without a complete project |

| 4) Installation | Transom height + shaft length | Prop stays properly immersed without unnecessary drag | Grip, stability, performance | Ventilation or excessive drag |

| 5) Setup | Propeller + trim adjustment | At full load, reach the recommended full-throttle range | Better hole shot, comfortable cruise, better efficiency | Wrong prop → engine labors or over-revs |

| 6) Purchase | New, used, reconditioned | Choose based on priority: peace of mind, budget, reset | Better control of total cost | “Low hours” but poorly stored or poorly maintained |

Quick FAQ

Can you install more power than the maximum shown on the builder’s plate?

No. Exceeding the approved maximum goes beyond what the boat was designed for (structure, stability, behavior). It can also impact safety and insurance.

Four-stroke: carburetor or electronic fuel injection—what changes day to day?

Electronic fuel injection is mainly about comfort and consistency: easier starts, steadier idle, more stable behavior, and often better-managed fuel use. A carburetor is simple, but it can be more sensitive to fuel aging, deposits, and long storage. For frequent use or fewer “surprises” after winter storage, electronic fuel injection is usually the calmer option.

Single engine or twin engines: when is a second engine truly justified?

A single engine is often perfect for coastal boating and mid-size boats. Twins make sense for redundancy, certain offshore fishing programs, and maneuverability—at the cost of higher purchase price, maintenance, weight, and fuel use.

How can you tell whether the propeller is suitable without being an expert?

Simple test: fully loaded, in acceleration, the engine should reach its recommended full-throttle revolution range without exceeding it. If it cannot reach it, the prop is often too “tall.” If it exceeds it, the prop is often too “short.”

What should you check before buying a used engine?

Focus on signs of harsh saltwater life: visible corrosion, improvised wiring, abnormal play, gearcase oil condition, water pump history, and whether hours match overall condition. Ideally, a sea trial and maintenance invoices remain the best filter.

What is a “normal” lifespan for a marine engine?

There is no universal number. A well-maintained engine, flushed after saltwater use, and operated in a coherent range can last a very long time. A low-use engine stored poorly can be a bad surprise.

Electric: how do you estimate realistic range?

Think in energy (battery capacity) and actual power draw. Electric propulsion shines at low speed and short runs, but range drops quickly if the goal is long, fast cruising. The right calculation is always at your cruising speed.

Why can engine weight matter as much as power?

On small hulls, a few extra kilograms on the stern can change running attitude, delay planing, and increase fuel use. A “perfect” engine on paper can be frustrating if it unbalances the boat.

What minimum maintenance should never be skipped in saltwater?

Freshwater flushing, healthy anodes, a monitored water pump, a clean fuel system, and corrosion protection: simple habits that often separate reliable engines from problematic ones.